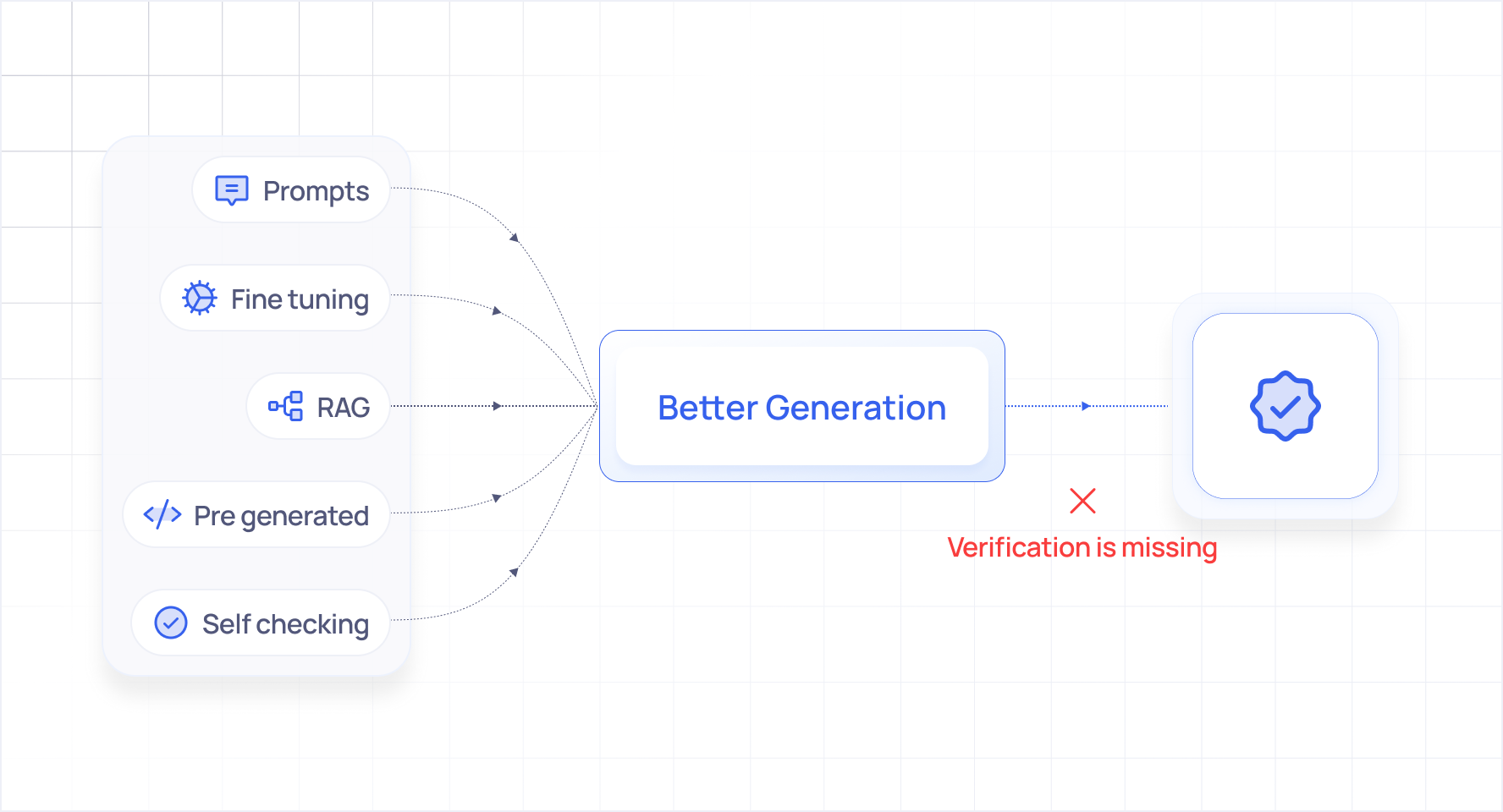

- Prompts, fine-tuning, RAG, and guardrails can improve LLM outputs, but they don’t make AI data analysis reliable.

- All current approaches focus on better generation, not on verifying whether the analysis actually matches user intent.

- Probabilistic interpretation means the same question can yield different answers, especially around definitions, time windows, and scope.

- Deterministic and fine-tuned systems reduce variance, but break down when users ask novel or exploratory follow-up questions.

- Trustworthy AI data analysis requires a verification layer that checks correctness throughout the process, not just at the end

This isn't a criticism of the people building these solutions. They're talented engineers solving genuinely hard problems. But the approaches themselves are mismatched to the nature of the challenge.

In our previous post, we outlined the 15 silent errors that plague AI powered data analysis. These range from quarter interpretation drift to JOIN type roulette to context loss in follow up questions. We established that these aren't edge cases or bugs to be patched. They're fundamental characteristics of how large language models operate.

The natural follow up question is what's been done about it.

Over the past two years, we've watched the industry cycle through multiple approaches to solving the accuracy problem. We've tried most of them ourselves. And we've arrived at an important conclusion. The dominant strategies for improving LLM reliability are fundamentally insufficient for data analysis use cases.

Approach #1. Better Prompts

The first instinct when an LLM misbehaves is to improve the prompt. Add more context. Be more specific. Include examples. Specify the output format.

Prompt engineering has become a discipline unto itself, and for good reason. It works. A well crafted prompt can dramatically improve output quality across many dimensions.

But here's the ceiling that prompt engineering hits in data analysis.

You cannot prompt away probabilistic behavior.

No matter how detailed your prompt, the model is still sampling from a probability distribution. Ask it the same question twice with the same prompt, and you'll get slightly different interpretations. The variance might be small, but in data analysis, small variances matter.

"Interpret 'last quarter' as the most recently completed calendar quarter" seems like a clear instruction. But what happens when the user's question contains conflicting signals? What if they mention a fiscal year elsewhere in the conversation? What if their company's quarter boundaries don't align with calendar quarters?

The prompt can't anticipate every contextual nuance. And the moment context becomes ambiguous, the model falls back to probabilistic interpretation.

We've tested prompts that are thousands of tokens long, meticulously specifying every edge case we could imagine. The accuracy improved, but the inconsistency remained. Same question, same prompt, different days, subtly different results.

Prompts are necessary but not sufficient. They're the foundation, not the solution.

Approach #2. Fine Tuning

If prompting can't eliminate variability, perhaps training can. Fine tune the model on your specific domain, your specific schemas, your specific business definitions.

Fine tuning does produce impressive results on the training distribution. A model fine tuned on your company's data can learn that "Q3" means fiscal Q3, that "revenue" excludes refunds, that "active user" has a specific 30 day definition.

The problem is brittleness.

Fine tuned models excel at scenarios they've seen. They struggle with scenarios they haven't. And in real world data analysis, users constantly ask questions that fall outside the training distribution.

"What if we excluded the APAC region?" "Can you break this down by the sales rep's tenure?" "Show me only customers who upgraded in the last 90 days and then churned."

These compositional, exploratory questions are precisely why users want AI analysts in the first place. They don't know exactly what they're looking for. They're exploring. They're following threads.

A fine tuned model that handles the common cases brilliantly but fails unpredictably on novel cases is arguably more dangerous than a general model that fails predictably. At least with the general model, users maintain healthy skepticism. The fine tuned model breeds false confidence.

There's also the maintenance problem. Schemas change. Business definitions evolve. New data sources get added. Each change potentially invalidates the fine tuning. You're not training a model once. You're committing to continuous retraining, with all the cost and complexity that entails.

Approach #3. Pre Generated Code and Deterministic Queries

We tried this approach ourselves about 16 months ago. The logic was appealing. If LLM generation is unreliable, minimize the generation.

The approach worked like this. For every metric a user might ask about, pre-generate the code (we used YAML based definitions). When a user asks a question, map it to the relevant pre generated metrics and execute deterministically. No LLM interpretation of the query logic itself, just mapping natural language to predefined computations.

On paper, this solves the consistency problem. The same question always maps to the same code, which always produces the same result.

In practice, it created a different problem. The constraint problem.

Users don't just ask about predefined metrics. They ask follow up questions. They want to slice data in ways you didn't anticipate. They combine concepts in novel ways.

"What's our churn rate?" That's handled beautifully. "What's our churn rate for enterprise customers who joined after the pricing change, excluding those who came through the partner channel, compared to the same period last year?" Not so much.

We thought we understood what "follow up questions" meant. We assumed it was filtering, adding a WHERE clause, changing a GROUP BY. We built robust support for that.

But real business users don't think in WHERE clauses. A follow up question in business context can be an entirely new analytical direction that happens to be conceptually related to the previous question. The user's mental model is associative, not hierarchical.

After onboarding pilot customers, we realized the limitation wasn't fixable through iteration. We weren't dealing with gaps in our metric library. We were dealing with a fundamental mismatch between deterministic computation and exploratory analysis.

The pre-generated approach works excellently for dashboards and standard reports. For ad hoc analysis and true data exploration, it hits an architectural ceiling.

Approach #4. Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG)

RAG has become the default architecture for grounding LLMs in specific knowledge. Retrieve relevant context, including documentation, schemas, and previous queries, then include it in the prompt. The model generates with the awareness of your specific environment.

For data analysis, this typically means retrieving schema information, column descriptions, business glossaries, and sometimes example queries.

RAG helps. It provides the model with context it wouldn't otherwise have. A model that knows your "customer_status" column has specific enum values will generate better queries than one guessing.

But RAG addresses the knowledge problem, not the verification problem.

Knowing that "Q3" should refer to fiscal quarters doesn't guarantee the model will apply that knowledge correctly in every case. Knowing that LEFT JOINs are preferred for this particular relationship doesn't prevent the model from occasionally choosing INNER JOIN anyway.

RAG improves the probability of correct generation. It doesn't verify that generation was correct.

The distinction matters. In creative applications, improving probability is enough. You want the model to be more likely to produce good outputs. In data analysis, probability isn't the standard. Accuracy is. A system that's correct 95% of the time is wrong 5% of the time. At enterprise scale, that's thousands of wrong answers.

Approach #5. Self Checking and Single Model Guardrails

The most sophisticated current approach involves having the model check its own work. Generate a query, then ask the model to review it. Look for logical errors, schema violations, potential misinterpretations.

This catches some errors. Models can identify obvious mistakes in their own outputs, including syntax errors, references to non existent columns, and logical contradictions.

But self checking has a fundamental limitation. Same model, same blind spots.

If the model misinterprets "last quarter" during generation, it's likely to accept that same misinterpretation during review. The blind spot isn't in the checking. It's in the understanding. And that understanding is shared across both generation and review.

This is why editors exist in publishing, why code review involves different people, why auditors are independent. Fresh perspective catches what self review misses.

A single model reviewing itself is better than no review. But it's not independent verification. It's the same perspective applied twice.

The Pattern Behind the Failures

Step back, and a pattern emerges across all these approaches.

They all try to make the generation better. None of them verify that generation was correct.

Better prompts lead to better generation. Fine tuning leads to better generation. Pre generated code bypasses generation but sacrifices flexibility. RAG leads to better informed generation. Self checking applies to the same model review of generation.

The implicit assumption is that if we can just make the generation good enough, verification becomes unnecessary. Get to 99% accuracy, and the 1% errors are acceptable.

But in data analysis, this assumption fails for two reasons.

First, the 1% isn't randomly distributed. Errors cluster around ambiguous cases, exactly the cases where users most need analytical help. Simple questions rarely fail. Complex, nuanced, high value questions fail at much higher rates.

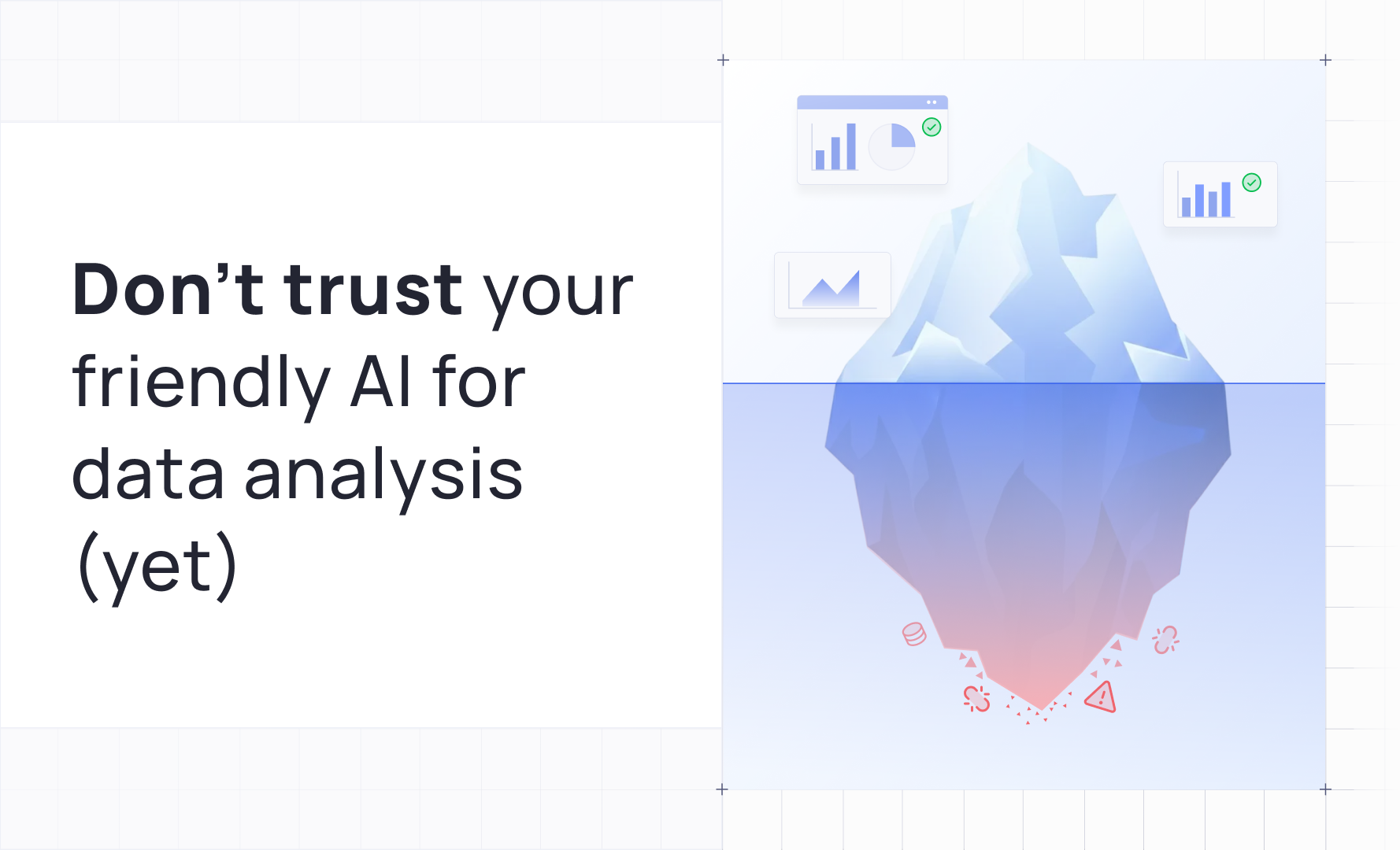

Second, users can't distinguish correct from incorrect outputs. Unlike code that crashes or text that's obviously nonsensical, wrong analytical results look exactly like right ones. A table with confident looking numbers provides no signal about whether those numbers are accurate.

Generation quality and output correctness are correlated but not equivalent. You can generate a beautiful, syntactically perfect, logically coherent query that answers the wrong question.

The Missing Layer. Verification

The alternative approach starts from a different premise. Assume generation will sometimes be wrong, and build systems to catch it.

This isn't a novel idea in software engineering. We don't trust individual components absolutely. We validate, cross check, and verify. Critical systems have redundancy built in. Financial calculations get reconciled. Medical diagnoses get second opinions.

But current AI data analysis architectures lack this verification layer. They're optimized for generation, with verification as an afterthought if it exists at all.

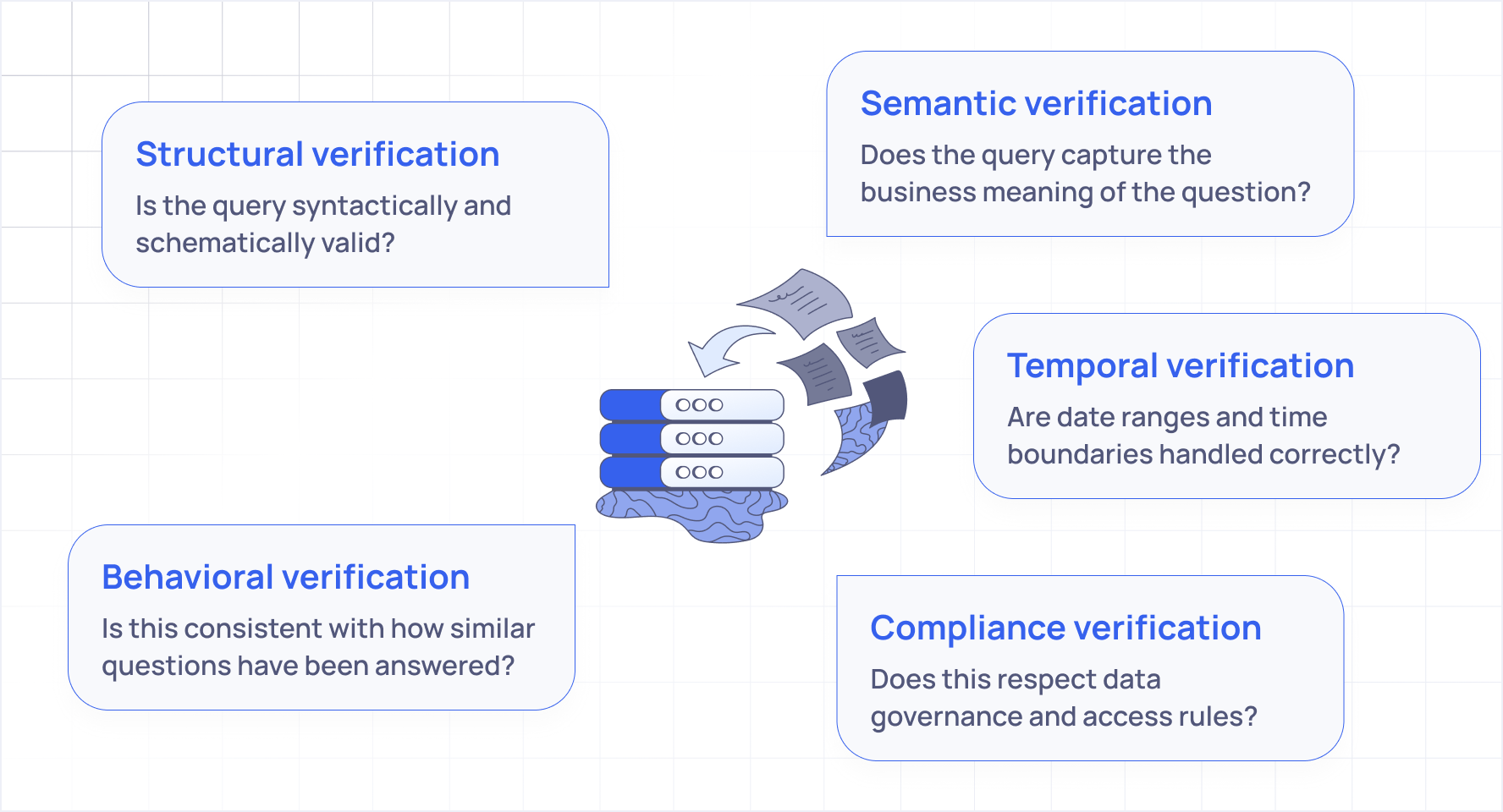

What would real verification look like?

Not a single check at the end, but distributed verification throughout the process. Not one model checking itself, but multiple specialized systems examining different dimensions of correctness. Not just "is this query valid?" but "does this query accurately represent the user's intent?"

The verification can't be bolted on. It needs to be architectural. Woven into every step of the analytical process, from understanding the question, to planning the approach, to generating the query, to validating the results.

And it needs to operate across multiple dimensions.

Each dimension requires different expertise. A structural validator looks for different things than a semantic validator. Trying to handle all dimensions with a single system creates the same blind spot problem we see with self checking.

This is the direction the field needs to move. From better generation to verified generation. From trusting outputs to validating them. From single model architectures to distributed verification systems.

The Path Forward

None of this means current approaches are worthless. Prompt engineering, fine tuning, RAG, and self checking all contribute to better outcomes. They're necessary layers in a complete solution.

But they're not sufficient. The verification layer is missing.

In our next post, we'll explore what that verification layer looks like architecturally. How do you build systems that verify analytical correctness across multiple dimensions? How do you distribute verification without creating latency bottlenecks? How do you make verification itself reliable?

These are hard problems. But they're the right problems. The ones that actually address why AI data analysis can't yet be fully trusted.

The goal isn't perfect generation. It's verified results.

This is Part 2 of a 4 part series on LLM Verification in AI powered data analysis.

← Part 1. The Hidden Crisis. Why AI Data Analysis Can't Be Trusted

Part 3. Distributed Verification. A New Architecture for Trustworthy AI Analysis (Upcoming) →

About Petavue

Petavue is building the verification layer for AI powered data analytics. Our platform ensures that when you approve an analysis plan, the results you get are exactly what you asked for. Verified at every step, consistent every time.

Currently in early release with design partners. Book a Demo at www.petavue.com

![[Data Story] Investigating San Francisco’s Feelers: Correlation Between Disorder, Crime and Administrative Strain](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/675e93d0c15c6d2e3ed70f0e/6942c4ce34e004dd8e77a3da_File.png)

![[SOTA Comparison] Gemini 3 Antigravity vs Claude Code 4.5: Can AI Really Build Production-Grade Modules?](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/675e93d0c15c6d2e3ed70f0e/692ef6868334a7120a65b676_File.png)